Table of Contents

Introduction

Last spring, schools were closed in all 50 states in the US due to the growing epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Only two states, Montana and Wyoming, reopened schools prior to the end of the academic year.

While schools in many areas of the country have now reopened, closures persist. In Washington, DC, in-person learning is still prohibited. The governments of Iowa, Arkansas, Texas, and Florida have ordered schools to be open for in-person learning, but in other states, school closures persist either due to state governments mandating closures for certain regions or certain age groups or due to that decision being made at the local level.

According to the New York Times, the view that schools should be reopened is radical and dangerous because of the risk of children transmitting SARS-CoV-2. Science, the Times would have us believe, strongly supports the continuation of school closures to help stop the spread of the virus.

After Dr. Scott Atlas, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, joined the Trump administration’s coronavirus task force, the Times published an article slamming him as a dangerous idealogue whose opinion about the need to reopen schools is contrary to the view of infectious disease experts and unsupported by science.

The fact that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), too, had called for schools to be reopened did not hinder the Times in its characterization of Atlas’s view. The Times explained this away as an instance of the CDC having caved to political pressure rather than following the science.

Similarly, the fact that the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) had also advocated reopening schools did not hinder the Times in so explaining the CDC’s guidance.

So, who is right? Does the New York Times accurately report the science? Do the data suggest that keeping schools closed is an effective and necessary measure to reduce transmission and prevent deaths from COVID-19?

These questions can be answered by carefully examining the Times’ arguments and the sources it provides to support its opposition to schools reopening. Doing so reveals that it is the New York Times whose position is extreme and unsupported by scientific evidence. The corollary is that the Times is more interested in advocating continued lockdown measures than in doing journalism.

The New York Times’ Arguments Against Reopening Schools

On September 2, the Times ran an article titled “A New Coronavirus Adviser Roils the White House With Unorthodox Ideas”, in which it characterizes Dr. Atlas’s opinion that schools should be reopened as extremely reckless. Atlas, we are told, is “a coronavirus contrarian” who has been “pushing a suite of disputed policy prescriptions”, including by calling for schools to be reopened.

“Mr. Trump is clearly enamored with Dr. Atlas’s arguments,” the Times states, “which back up the president’s desire to restart the economy, open schools and move beyond the daily drumbeat of dire virus news.”

The danger was illustrated by Sweden, where the government “allowed restaurants, gyms, shops, playgrounds and schools to remain open”. The “libertarian-style approach” advocated by Dr. Atlas, which was to focus on protecting at-risk populations while allowing others to go on with their lives, was “an approach used to disastrous effect in Sweden.”

Dr. Atlas has argued “that children cannot pass on the coronavirus”, which is among his ideas that are “ideologically freighted and scientifically disputed” and considered “misguided” and “even dangerous” by “top government doctors and scientists like Anthony S. Fauci, Deborah L. Birx and Jerome Adams, the surgeon general”.

Near the end of the article, the Times elaborates:

In other discussions, he argued that children cannot spread the virus, despite numerous studies that have shown that children can carry the virus, transmit it and die from it.

In a June interview with the Hoover Institution, he called it “literally irrational” to close schools. “All over the world, Switzerland, Iceland, Australia, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Asian countries, there is a minimal, if any, risk of children transmitting the disease, even to their parents,” he said.

Dr. Atlas brought a similar argument to an August event encouraging school reopenings with Mr. Trump and Betsy DeVos, the education secretary.

In sum, Atlas’s view on reopening is contrary to that of top experts, and his arguments are contradicted by the science.

On September 28, the Times published an article titled “Behind the White House Effort to Pressure the C.D.C. on School Openings”, which carried the same theme that pushing for schools to be reopened is dangerous and contrary to the science.

The Trump administration, we are told, made a concerted effort to “circumvent” the CDC by searching for “alternate data” showing that SARS-CoV-2 “posed little danger to children.”

The White House also urged top CDC officials to produce data “that could show the low risk of infection and death for school-age children” and “to show people 18 and under as a separate group” in its estimates of the COVID-19 fatality rate.

The White House argued “that school closures would have a long-term effect on the mental health of children”. Furthermore, it claimed “that ‘very few reports of children being the primary source of Covid-19 transmission among family have emerged’” and “that children who were asymptomatic ‘are unlikely to spread the virus.’”

Halfway into the article, the Times acknowledges that the AAP, too, has called for schools to reopen. But the Times adds that the AAP “warned that areas with high infection rates would not be able to open safely”. Furthermore, an alarming trend has since appeared: “data compiled by the academy from recent months shows that hospitalizations and deaths from the coronavirus have increased at a faster rate in children and teenagers than among the general public.”

Additionally, “A large study from South Korea published in July showed that children between the ages of 10 and 19 can spread the virus at least as much as adults do. (A later study called those conclusions into question, but the July study was more widely reported.)”

Bowing under pressure from the White House, when the CDC on July 23 issued updated guidance on reopening schools, “it contained information that C.D.C. officials had objected to earlier in the week, suggesting in particular that the coronavirus was less deadly to children than the seasonal flu.”

In sum, the message that the New York Times delivers to its readers is that the view shared by Dr. Scott Atlas and President Donald Trump that schools should be reopened is radical, dangerous, and contradicted by the science; the AAP’s criterion for reopening schools have not been met; and the CDC’s advocacy of school reopenings is a product of politicization, not science.

However, the New York Times is demonstrably lying.

Getting It Wrong on Sweden

To support its claim that keeping schools open contributed to a “disastrous” outcome in Sweden, the Times links to a July 7 article headlined “Sweden Has Become the World’s Cautionary Tale”.

Sweden, we are told, has been “conducting an unorthodox, open-air experiment” on its population by choosing not to follow other countries into lockdown regimes. And this mass experiment has had a “grim result”, with rate of deaths per capita in “Scandinavia’s pariah state” that exceeded the rate in neighboring Norway, Finland, and Denmark. Additionally, “Sweden has suffered 40 percent more deaths than the United States” on a population-adjusted basis.

The suggestion that it was Sweden that took the unorthodox approach is certainly puzzling, though, since it was the countries that enforced strict lockdowns who were implementing unprecedented measures unsupported by scientific evidence. It was Sweden that followed more established and orthodox guidelines for confronting respiratory virus epidemics. It was the lockdown countries that chose to treat their citizens as subjects of a mass uncontrolled experiment without consideration for the extraordinary harms that would predictably result.

It is true that Sweden’s rate of deaths per capita is higher than that of its neighbors. But it’s important to keep in mind that we were also told early on by lockdown advocates that if Sweden didn’t follow other countries into lockdown to “flatten the curve” and prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed, the result would be “catastrophe” and “a historical massacre”.

The UK had been on a similar policy course as Sweden until mid-March, when the influential model by Neil Ferguson and his coauthors at Imperial College, London, came out. That model, which projected massive numbers of deaths if lockdown policies weren’t implemented, has been credited with prompting the UK to change its course.

In mid-April, other researchers published projections from a model, based on the one from Imperial College, warning that if Sweden didn’t follow the UK into lockdown, it would see 96,000 COVID-19 deaths by the end of June.

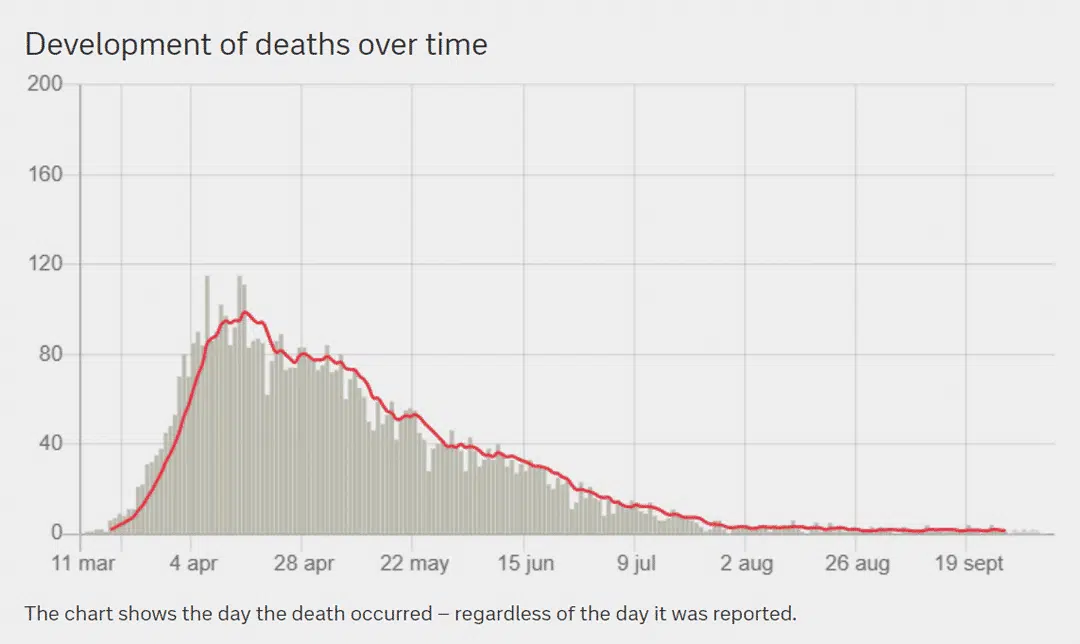

In fact, Sweden’s hospitals were never overwhelmed. The Swedish people successfully flattened the curve without their government resorting to extreme authoritarian measures. The predicted “historical massacre” never happened, and as of October 10, there was a total of 5,894 COVID-19 deaths reported in Sweden—more than sixteen times fewer deaths than the model projected Sweden would surpass by July 1.

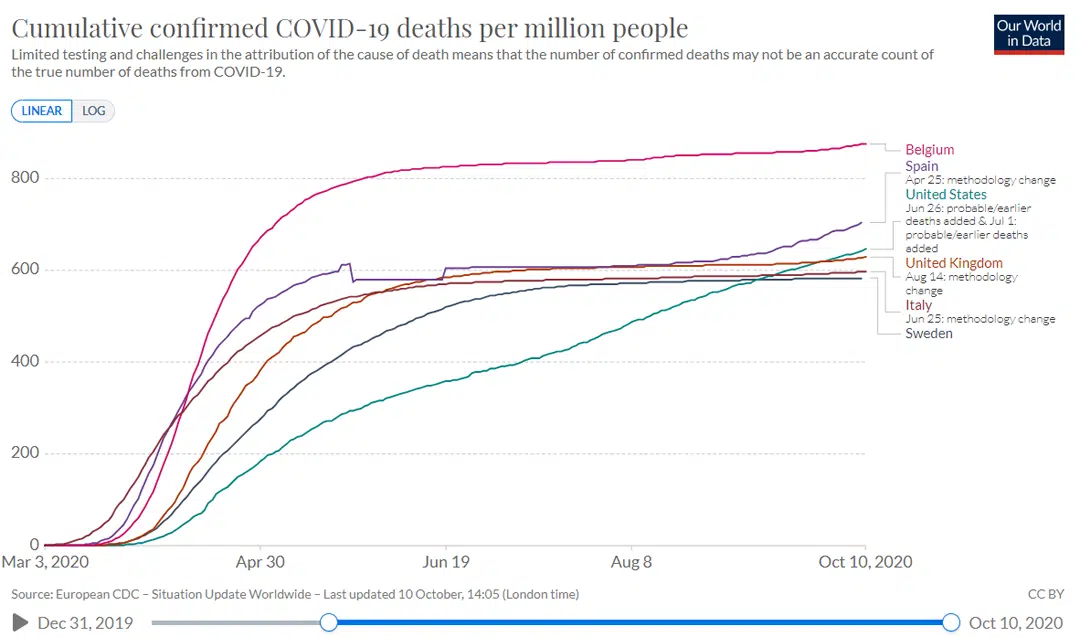

While Sweden’s death rate per capita is indeed higher than its Scandinavian neighbors, it remains lower than that of the UK, as well as European lockdown countries Belgium, Spain, and Italy.

At the end of April, the Times acknowledged that, “to a large extent, Sweden does seem to have been as successful in controlling the virus as most other nations”—without resorting to the same drastic measures. It’s death rate per capita was “the same as that of Ireland”, a lockdown country that had “earned accolades for its handling of the pandemic”, and Sweden was faring “far better” than lockdown countries Britain and France.

In mid-May, the Times acknowledged that, while suffering a deadlier outbreak than its Scandinavian neighbors, Sweden was “still better off than many countries that enforced strict lockdowns.”

In late June, the Times again pointed to the lower rate of deaths per capita among its neighbors to decry Sweden as “Scandinavia’s pariah state.” But as noted by the architect of Sweden’s approach, Dr. Anders Tegnell, a beneficial consequence was a higher rate of population immunity, which was already “contributing to lower numbers of patients needing hospitalization, as well as fewer deaths per day.”

On July 8, one day after decrying Sweden as a “pariah state”, the Times acknowledged that, even accounting for the US’s greater population, the data showed that Sweden was “in significantly better condition than the United States.”

In that article, the Times also acknowledged that there was “little evidence that school reopenings in Europe have resulted in widespread increases in coronavirus cases.”

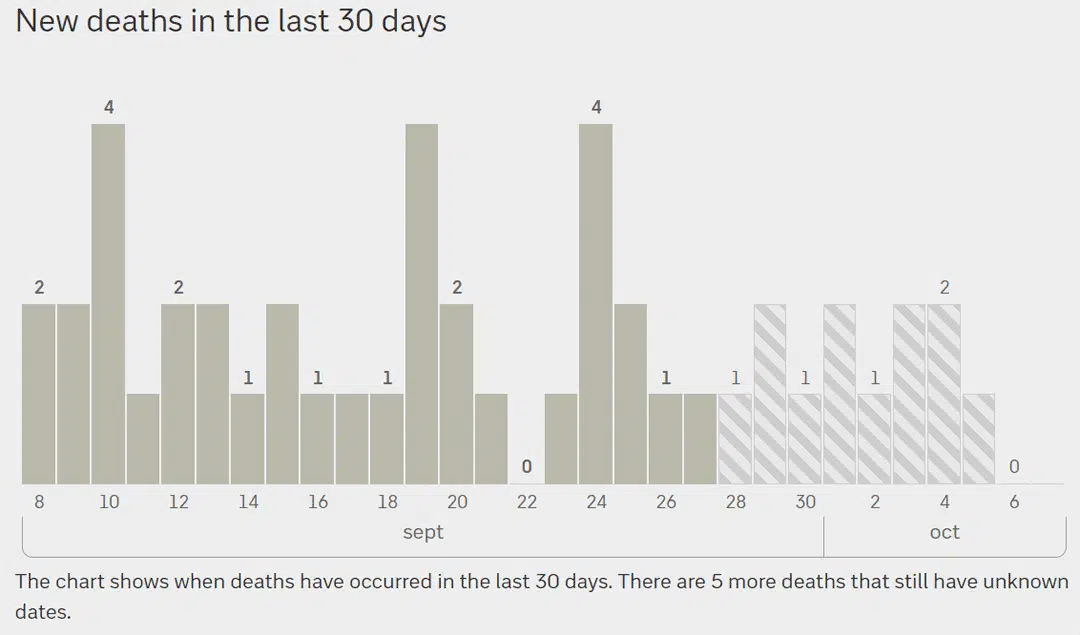

Undoubtedly at least in part due to a higher level of population immunity, throughout September, Sweden saw between zero and four COVID-19 deaths per day, whereas by September 11, the US had surpassed Sweden in its per capita death rate.

In sum, the absolute catastrophe that lockdown advocates said would result from Sweden’s refusal to implement authoritarian measures never happened, and far from implementing a failed policy, Sweden successfully flattened the curve.

Moreover, Sweden’s higher rate of deaths per capita is predominantly attributed to a high rate of deaths among residents of long-term care facilities.

According to data current up to August 13, by which time daily deaths had been declining for four months, there had been 5,776 COVID-19 deaths in Sweden. Of those, 42 percent were aged 80 to 89 years, and 89 percent were aged 70 or older. Only 2 percent were under the age of 60. Among the deceased, 85 percent had one or more of the following underlying medical conditions: cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, or respiratory disease; 25 percent were receiving in-home care service; and 47 percent were living in care homes.

Whereas the New York Times and other lockdown advocates would have us believe that the deadly outcome for nursing home residents was a consequence of Sweden’s decision not to implement a strict lockdown, the truth is lockdown measures have also failed to protect those at highest risk.

In fact, according to the Times’ own compiled data, about 40 percent of COVID-19 deaths in the US are linked to nursing homes.

In some states, such as New York and New Jersey, policymakers were so narrowly focused on opening up beds so that hospitals wouldn’t be overwhelmed that they ordered nursing homes to accept COVID-19 patients discharged from hospitals.

According to data published by the Kaiser Family Foundation in mid-June, nursing home residents or staff represented 21 percent of COVID-19-related deaths. New York in turn represented more than a quarter of all deaths in the US. In New Jersey, as well as 23 other lockdown states, more than half of COVID-19-related deaths were among nursing home residents.

In sum, the outcome in Sweden is, by the Times’ own criteria, less disastrous than the outcome that lockdown measures have achieved in the US. Moreover, the Times presented no evidence showing that Sweden’s death rate was in any way related to schools remaining open.

Quoting Dr. Scott Atlas Out of Context

To support its characterization of Dr. Atlas as a dangerous ideological extremist, the Times cites an interview he gave in June with Peter Robinson of Uncommon Knowledge at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. The Times contradicts itself, though, which is a clue that Atlas is being quoted out of context.

First, the Times states that Dr. Atlas maintained “that children cannot spread the virus”; but then it quotes him acknowledging the possibility that they can by describing the risk as “minimal”.

Turning to the interview transcript, Dr. Atlas did say that children “do not even transmit the disease”, but the fact that he did not mean that as an absolutism is clearly demonstrated by the context in which he said it.

Just prior to that statement, Dr. Atlas said that schools should be opened “because there is virtually zero risks of death and virtually zero risks of a serious illness in children. This is the fact. This is inarguable. This is proven not only every country outside the United States but by our own data in the CDC itself.”

Indeed, it is inarguable that the risk to children of dying from COVID-19 is virtually zero. This is shown even by the data compiled by the AAP that the Times cites to support its argument, as well as by the CDC’s own estimate of the infection fatality rate among children, both of which we’ll come back to.

Referencing the experience of numerous European countries in opening schools, Atlas said that “there is a minimal, if any, risk of children transmitting the disease, even to their parents.”

The Times, recall, had conceded on July 8 that there was “little evidence that school reopenings in Europe have resulted in widespread increases in coronavirus cases.”

Atlas continued, “It’s not just that children are not at risk at all from this disease. They also do not even transmit the disease. It is literally irrational to not only close schools . . .”

At that point, Robinson interrupted to ask about the risk to teachers of becoming infected by schoolchildren. Atlas continued, “There’s not a significant risk, but I wanna qualify that. Let’s look at who the teachers are in K-12 schools in the United States. Half of them are 41 years old or younger. 82% are under 55. The risk from COVID-19 for people under 60 is less than or equal to seasonal influenza. So if you’re gonna shut down the schools because you’re worried about the rare teacher who’s in a high-risk category, you must necessarily close the schools from November through April because they’re in the same risk in flu season.”

Indeed, the CDC’s estimated infection fatality rate for adults aged 20 to 49 years is 0.02 percent, which is considerably less than the 0.1 percent that the New York Times reports as the infection fatality rate of influenza. The CDC’s estimate for adults aged 50 to 69 years is higher, at 0.5%, but that includes people in their sixties, whereas Atlas specified those under age 60.

Atlas continued by noting that some teachers would be in high-risk groups, and it was “less likely” but “not impossible” that children could transmit the virus to them. However, these teachers could either maintain social distancing or teach remotely “instead of shutting down schools.”

He proceeded to discuss what “no one’s talking about”, which is “the harms of closing the schools.”

Instructively, in its hit piece on Atlas, the Times chose not to mention that many harms from school closures were well established in the scientific literature.

Falsely Citing Viral Load Data as Proof of Contagion

This brings us to the Times’ statement that Dr. Atlas has “argued that children cannot spread the virus, despite numerous studies that have shown that children can carry the virus, transmit it and die from it.”

As we have now seen, Atlas did not deny that children can carry, transmit, and die from SARS-CoV-2. He rather acknowledged this. In the interview, he was not rejecting the possibility but stressing that the data showed that the risk of children transmitting the virus was low.

The hyperlink that the Times provides to support its case goes to a July 30 article by Apoorva Mandavilli—whose articles have been consistently propagandistic. She has systematically misreported the science in order to advocate lockdown policies, as I have extensively documented in part one, part two, part three, and part four of my series titled “How the New York Times Lies about SARS-CoV-2 Transmission”.

The title of Mandavilli’s article was “Children May Carry Coronavirus at High Levels, Study Finds”, which reported the findings of a study published in JAMA Pediatrics on July 30. The study, however, does not contradict Dr. Atlas’s statements about the evidence indicating that children are not major drivers of transmission.

In fact, in providing the background context for their study, the authors noted the absence of “strong evidence” that children are “major contributors to SARS-CoV-2 spread”.

The Times itself even acknowledges right at the top of the page in its article summary that the study “does not prove that infected children are contagious”.

Mandavilli’s lead paragraph further acknowledges that the prevailing view among scientists is that young children “are mostly spared by the coronavirus and don’t seem to spread it to others, at least not very often.” (Emphasis added.)

The new study found that the viral load in the noses and throats of infected children was equal or higher than that in infected adults. However, the Times admits, this “does not necessarily prove children are passing the virus to others.”

This is because the viral load was inferred from the use of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays, which detect viral RNA but cannot determine whether the detected RNA is indicative of non-viable viral fragments or infectious virus capable of being transmitted and causing infection in others.

Likewise, two other studies Mandavilli cites, one from Germany and one from France, also did not show that children are contagious, only that children’s viral loads were at least as high as adults’.

Further into the article, Mandavilli acknowledges that “Observations from schools in several countries have suggested that, at least in places with mild outbreaks and preventive measures in place, children do not seem to spread the coronavirus to others efficiently.” (Emphasis added.)

In sum, the Times statement that “children can carry the virus, transmit it and die from it” did not contradict what Dr. Atlas had said.

Atlas was right to say that data showed that the risk to children from SARS-CoV-2 is low.

He was also right that evidence strongly indicates that children are not a major driver of transmission, and the study cited by the Times did not show otherwise.

On the contrary, the Times’ implicit claim that the viral load studies proved that children are just as contagious as adults is false, as acknowledged by its own reporter.

The New York Times vs. the AAP

Since Dr. Atlas’s view happened to accord with the position of both the CDC and the AAP that children should be attending school, it was necessary for the Times to take on the difficult task of explaining those organizations’ positions in a way that could be reconciled with its description of Atlas as holding a dangerously contrarian view.

Hence, we are told in the article “Behind the White House Effort to Pressure the C.D.C. on School Openings” that the Trump administration tried to “circumvent” the CDC by searching for “alternate data” showing that SARS-CoV-2 “posed little danger to children” and then pressured the CDC to show age-stratified infection fatality rates and say that COVID-19 is less deadly to children than the seasonal flu. Moreover, the White House had the gall to take the harms of school closures into account and argued that studies indicated that children are not drivers of community transmission.

While the Times acknowledges halfway through the article that the AAP has advocated for reopening schools, it directs readers’ attention to the part of the AAP’s guidance that “warned that areas with high infection rates would not be able to open safely.”

The AAP’s guidance document, updated on August 19, is titled “COVID-19 Planning Considerations: Guidance for School Re-entry”. The sentence we are supposed to know about reads, “Although the AAP strongly advocates for in-person learning for the coming school year, the current widespread circulation of the virus will not permit in-person learning to be safely accomplished in many jurisdictions.”

What the Times obviously did not wish us to know about is all the other information in the AAP’s guidance that supported Dr. Atlas’s and the White House’s position on school reopenings.

The AAP emphasized the known harms of school closures.

It noted that “the preponderance of evidence” indicated that children “are less likely to be symptomatic and less likely to have severe disease resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

It also emphasized that it “does not appear to be the case” with SARS-CoV-2 that “children and adolescents play a major role” in amplifying outbreaks. Rather, the evidence indicated “that children younger than 10 years may be less likely to become infected and less likely to spread infection to others”.

Interestingly, the Times does not describe the AAP as pushing an “unorthodox”, “contrarian”, “misguided”, and “dangerous” view.

Rather, in a June 30 article titled “Why a Pediatric Group Is Pushing to Reopen Schools This Fall”, the Times described the AAP as an organization with a “conservative and cautious” reputation that “made a splash” with guidance that was “at odds with” the position of “some federal and state health officials”—such as the CDC, which had “advised that remote learning is the safest option.”

However, it was not true that the CDC was advising that schools should remain closed. On the contrary, the CDC, too, had issued guidance for how decisions could be made at the local level to enable in-classroom learning while mitigating the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

The article included an interview with Dr. Sean O’Leary, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who helped write the AAP’s guidelines for reopening schools and who was a father of two children and a survivor of COVID-19. As Dr. O’Leary said, “School-age kids clearly play a role in driving influenza rates within communities. That doesn’t seem to be the case with Covid-19. And it seems like in countries where they have reopened schools, it plays a much smaller role in driving spread of disease than we would expect.”

With hyperlinked references to supporting studies, the Times further quoted Dr. O’Leary as saying, “What we have seen so far in the literature—and anecdotally, as well—is that kids really do seem to be both less likely to catch the infection and less likely to spread the infection.”

The first link provided is to a study published on June 25 in Clinical Infectious Diseases that reported how investigators in Singapore “could not detect SARS-CoV-2 transmission” in schools. In preschools, infections, too, were “undetectable.” The study authors summarized their findings by saying that “the risks of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among children in schools, especially preschools, is likely to be low.”

The second link is to a systematic review of evidence on the use of school closures to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2, published on May 1 in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. Researchers found “a remarkable dearth of policy-relevant data” on school closures. Most evidence came from studies on influenza, but data on COVID-19 indicated that children may be less likely to become infected and more likely to be asymptomatic if they are infected. Children are thus also “less likely to spread the virus through coughing or sneezing. Data from the SARS outbreak suggested that school closures “did not contribute to control of infection transmission.”

Moreover, closing schools could backfire if it meant grandparents taking on a greater childcare role. This could result in an increased risk of transmission that was “a particular concern for COVID-19, with its higher mortality among older people”. In the UK, 40 percent of grandparents “provide regular childcare for their grandchildren.”

While “evidence to support national closure of schools to combat COVID-19 is very weak”, the “economic and potential harms of school closure are undoubtedly very high” and had “profound economic and social consequences.”

The third link is to an article published on May 5 in Archives of Disease in Childhood titled “Children are not COVID-19 super spreaders: time to go back to school”. Its authors also noted that closures were implemented based on the assumption that, as for influenza, children would be “primary drivers of household SARS-CoV-2 transmission”. But this was an assumption for which policymakers were “without evidence”.

Rather, accumulating evidence from countries all over the world suggested that “children could be significantly less likely to become infected than adults” and may also be less likely to transmit the virus. Data indicated that “children were not likely to be the index case in households”. Given the available evidence, governments worldwide “should allow all children back to school”.

The fourth link is to a modeling study published on June 16 in Nature Medicine in which researchers estimated that “susceptibility to infection in individuals under 20 years of age is approximately half that of adults aged over 20 years”. Furthermore, only 21 percent of infected children aged 10 to 19 years developed symptoms compared to 69 percent of adults over age 70. Consequently, the impact of school closures on reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission might be “relatively small”.

The fifth is to an article published on July 31 in the AAP’s journal Pediatrics titled “COVID-19 Transmission and Children: The Child Is Not to Blame”. Its authors noted that “children appear to be infected” by SARS-CoV-2 “far less frequently than adults and, when infected, typically have mild symptoms”. While the extent to which children are responsible for transmission remained unknown, accumulating evidence suggested that “children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them.”

In a contact tracing study in Switzerland, children were identified as the presumed index patient in only 8 percent of cases. As the authors noted, “transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children outside household settings seems uncommon”. Overall, the data “suggest that children are not significant drivers of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The “accumulating evidence and collective experience argue that children, particularly school-aged children, are far less important drivers of SARS-CoV-2 transmission than adults. Therefore, serious consideration should be paid toward strategies that allow schools to remain open, even during periods of COVID-19 spread.”

Returning to the article “Behind the White House Effort to Pressure the C.D.C. on School Openings”, we can see how the Times glossed over the information in the AAP’s guidance document and the accumulating scientific evidence that didn’t fit its preferred narrative.

After highlighting a single sentence from the AAP document that could appear reconciled with that narrative, the Times quickly moved on to cite “data compiled by the academy from recent months” showing “that hospitalizations and deaths from the coronavirus have increased at a faster rate in children and teenagers than among the general public.”

But as I have previously documented in my article “NY Times Lies about the Risk of Children Dying from COVID-19”, that data, too, supported the position of Dr. Atlas and the White House.

The link provided is to a Times report about that data, published on August 31 and titled “U.S. Coronavirus Rates Are Rising Fast Among Children”. While the Times puts an alarmist spin on the trend shown, a more honest interpretation is that this is a good thing because it means that an increasing proportion of cases are occurring among younger people who are at far less risk of severe disease and death than older adults.

In other words, what the trend in the data indicate is a decreasing case fatality rate for COVID-19.

The data also show that Dr. Atlas and the White House are right to say that the risk to children of dying from COVID-19 is near zero. The average case fatality rate among children in states reporting the data, plus New York City, is 0.01 percent. Given 780 reported cases for every 100,000 children in the population, the child population mortality rate is about 1 death for every 1,282,051 children, or a risk of death of about 0.000078 percent.

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that the 0.01 percent is an estimated case fatality rate, which inherently overestimates the fatality rate since it includes only reported cases in the denominator. So, the true fatality rate is likely considerably lower.

In sum, to support its argument, the Times cherry picked what it wanted to see out of the AAP’s guidance while ignoring the rest of the document and the overwhelming scientific evidence leading strongly to the conclusion that policymakers have likely done considerably more harm than good by closing schools.

Misinterpreting and Misreporting the South Korea Study

Next, the Times cites a study from South Korea supposedly having shown “that children between the ages of 10 and 19 can spread the virus at least as much as adults do.”

The link is to a July 18 article by Apoorva Mandavilli titled “Older Children Spread the Coronavirus as Much as Adults, Large Study Finds”. That article reported on a study titled “Contact Tracing during Coronavirus Disease Outbreak, South Korea, 2020”, which was published on July 16 in the CDC’s journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

However, that study’s findings do not lead to the conclusion that children are significant drivers of SARS-CoV-2 transmission when schools are opened.

One of the study’s limitations is that the authors “could not determine direction of transmission”. Rather, they made assumptions about who transmitted the virus to whom by defining an “index case” as “the first identified laboratory-confirmed case or the first documented case in an epidemiologic investigation within a cluster.”

Just because someone is the first person identified in a cluster of cases does not necessarily mean that person was the index case who began the chain of transmission.

Mandavilli relayed this limitation to her readers by saying, “The first person in a household to develop symptoms is not necessarily the first to have been infected, and the researchers acknowledged this limitation.”

That prior acknowledgment, however, didn’t stop the Times, in its article on the White House pressuring the CDC, from characterizing the study as having proven that children are equally contagious as adults.

While the Times also parenthetically notes that a later study “called those conclusions into question”, it curiously declined to elaborate or provide a link to that later study. (I tried but was unable to determine what study the Times might be referring to.) Instead, the Times opted to downplay it on the equally puzzling grounds that it wasn’t as “widely reported”—as though the criteria we should use to determine whether a conclusion is true or not is how much attention it gets in the media.

And while the Times interprets the study from South Korea as showing that the risk of children spreading SARS-CoV-2 would be too great if schools were reopened, the study in fact does not represent transmission dynamics within the school setting.

On the contrary, it investigated clusters in the household setting at a time when “lockdown” measures, including school closures, were in effect.

As the study’s authors commented, their findings “largely reflected transmission in the middle of mitigation and therefore might characterize transmission dynamics during school closure. Higher household than nonhousehold detection might partly reflect transmission during social distancing, when family members largely stayed home except to perform essential tasks, possibly creating spread within the household.” (Emphasis added.)

Thus, it was not the case that children were bringing the virus home from school and spreading it within households. Rather, it would have primarily been adults becoming infected while out doing “essential tasks” and bringing the virus into the household.

Furthermore, as the authors also noted, prior studies had shown a “high infection rate within families”. In the US, studies had shown that the infection rate for symptomatic household contacts is “significantly higher than for nonhousehold contacts.”

In other words, to support its position that reopening schools would result in children transmitting the virus at an unacceptable rate, the Times cites a study that cannot be used to draw conclusions about transmission dynamics in the school setting because it investigated transmission dynamics in the household setting during a time of lockdown including school closures.

When the Times claims that children aged 10 to 19 have been shown to transmit the virus at least as much as adults, it is referring to Table 2 of the study. It shows that 231 of those children’s collective household contacts were traced and that, among those contacts, 43 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The rate of positive results among these contacts was thus 18.6 percent, which was the highest of any age group.

On the other hand, among contacts of children aged 9 or younger, only 3 of 57—or 5.3 percent—tested positive, which was the lowest of any age group.

If we apply the Times’ own interpretation of the data, we must conclude that younger children are less than half as likely to transmit the virus as adults aged 30 or older. Indeed, in her report on the study, Mandavilli said it found that younger children “transmit to others much less often than adults do, but the risk is not zero.”

This finding would seem to support the argument that kindergartens and elementary schools should be open, but zero is evidently where the risk level would need to be before the Times could agree that school closures should not persist.

Never mind that, as observed in JAMA (the journal of the American Medical Association), “The harms associated with school closures are profound.”

The profound expected harms included an estimated $2.5 trillion in lost future earnings; an additional $128 billion in lost productivity for every 12 weeks of school closure due to the loss of parents’ ability to work; and the expectation of “long-term deleterious consequences for child health, likely reaching into adulthood.” School closures also disproportionately harm children from low-income families and so “could significantly widen inequalities.”

The Times also withheld another important finding from the South Korea study, presented in Table 1. It shows that children aged 10 to 19 comprised just 2.2 percent of assumed “index patients”. Children aged 9 or younger comprised just 0.5 percent.

In other words, 97.3 percent of index patients were adults.

The Times’ headline is therefore false. The study did indicate that “household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was high if the index patient was 10–19 years of age.” But it did not show that “Children Spread the Coronavirus Just as Much as Adults”. These are not the same thing.

Rather, what the study indicated is that, even if symptomatic children are equally capable of transmitting the virus as adults, children were still a minor contributing factor in the spread of the virus within the investigated clusters.

In other words, if the identified index patient was aged 10 to 19 years, then the proportion of their contacts who also tested positive was similar to clusters in which adults were identified as the index patients. However, children in this age range were still less likely to be identified as the index patient in the first place.

Thus, what the study really showed, contrary to the claim made in the Times’ headline, is that children did not spread the virus as much as adults.

The authors did not comment on the reasons for this. Their data indicate that children had far fewer contacts than adults, which makes sense under the circumstances of a lockdown, when children were home from school and only adults were allowed to leave the home to perform “essential” tasks.

Furthermore, as noted by the AAP, the cumulative evidence suggests that children are less likely to become infected and less likely to develop symptoms if infected.

Whereas the Times ignores that science and scorns the Trump administration for urging the CDC to emphasize that asymptomatic children are unlikely to spread the virus, the World Health Organization (WHO) has observed that “It still appears to be rare that an asymptomatic individual actually transmits onward.”

(The New York Times tried to deceptively spin that information from the WHO, too, as part of its effort to manufacture consent for extreme lockdown measures, as I discussed in great depth in my article “How the New York Times Lies about SARS-CoV-2 Transmission: Part 4”.)

As Carl Heneghan and Elizabeth Spencer of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at the University of Oxford point out, the study from South Korea “has been cited in the media as the basis for believing that younger children posed low risks of transmission but that children of secondary school age were likely to transmit at rates similar to adults.”

However, the study “was not designed or powered to make such a comparison”.

Furthermore, “the study was conducted during lockdown when all stayed at home except for essential tasks”, and “the context was not in schools”. Therefore, it “should not be interpreted to understand risk in schools.”

In other words, the study should not be cited for the purpose for which the New York Times cites it.

The New York Times vs. the CDC

In the final paragraph of its article characterizing the CDC’s guidance on school openings as having been a product of politicization instead of science, the Times bewails that the guidance suggested COVID-19 is “less deadly to children than the seasonal flu.”

The Times thus treats that conclusion as controversial. It is not.

As observed in a May 11 study published in JAMA Pediatrics, children “face a far greater risk of critical illness from influenza than from COVID-19”.

Are we also to believe that the Trump administration pressured the authors and journal editors into publishing that statement? Or, if we accept that conclusion as true since it’s what the scientific data tell us, what is the problem with the White House urging to CDC to emphasize the fact? Does truth not matter? Evidently, to the Times, it does not—at least not when truth runs counter to whatever political agenda it happens to be advocating under the guise of “journalism”.

Again, even the data cited by the Times to bolster its case shows that the case fatality rate among children is 0.01 percent. And that is an inherent overestimate of the true fatality rate since it includes only reported cases in the denominator.

The current “best estimate” presented by the CDC for the infection fatality rate, which aims to account for the total number of estimated infections and not only reported cases, is 0.003 percent.

The CDC presented that estimate in a document it updated on September 10. The New York Times would have us believe that the White House should be condemned for pressuring the CDC to produce age-stratified estimated infection fatality rates. But why shouldn’t the CDC have already done so before its September 10 update? Indeed, why did it take so long for the CDC to take this sensible step?

It is surely of great importance, after all, to be able to assess the risk to individuals based on their age, along with other risk factors. If indeed this update was a consequence of the White House having urged the CDC to do so, why shouldn’t the Times recognize the White House as having done a good deed rather than complaining about it?

Of course, the motive for the statist New York Times to instead criticize is obvious: it is more interested in maintaining its advocacy of lockdown measures than in doing honest journalism.

That ulterior motive also explains why the Times suggests that by seeking to emphasize the low risk to children from COVID-19, the White House was searching for “alternate data” when, in fact, that is the conclusion of mainstream medical science.

Indeed, when the New York Times published its hit piece dismissing Dr. Atlas’s views as dangerously unorthodox, it was the Times that was acting in the contrarian role and taking up a position at odds with the CDC—which the mainstream media typically portray as the ultimate authority on infectious diseases and, indeed, as a virtually infallible institution when it comes to the topic of the CDC’s recommendations for routine use of vaccines in children.

On July 23, the CDC had issued its guidance emphasizing “The Importance of Reopening America’s Schools this Fall”. As the CDC pointed out,

Scientific studies suggest that COVID-19 transmission among children in schools may be low. International studies that have assessed how readily COVID-19 spreads in schools also reveal low rates of transmission when community transmission is low. Based on current data, the rate of infection among younger school children, and from students to teachers, has been low, especially if proper precautions are followed. There have also been few reports of children being the primary source of COVID-19 transmission among family members. This is consistent with data from both virus and antibody testing, suggesting that children are not the primary drivers of COVID-19 spread in schools or in the community.

We could stipulate that the CDC published those statements due to pressure from the White House, and it wouldn’t make that information any less true.

The September 28 article “Behind the White House Effort to Pressure the C.D.C. on School Openings” echoed its original July 24 report on the CDC’s new guidance, titled “C.D.C. Calls on Schools to Reopen, Downplaying Health Risks”.

Of course, the phrase “Downplaying Health Risks” was being used euphemistically to mean “Emphasizing the Low Health Risks”, whereas the New York Times has exaggerated those risks while truly downplaying the known harms associated with school closures.

Below that headline, the article summary read, “The agency’s statement followed earlier criticism from President Trump that its guidelines for reopening were too ‘tough.’” The lead paragraph informed that the statement had “aligned” the CDC “with President Trump’s pressure on communities, listing numerous benefits of being in school and downplaying the potential health risks.”

Instructively, the Times did not present any evidence that the CDC’s information was wrong and that the health risks from COVID-19 clearly outweigh the harms from school closures. Instead, the Times settled for describing the CDC’s conclusion that children are “at low risk for being infected by or transmitting the virus” as being a question of science that “is far from settled.”

That is true enough, but also inconsequential. Eight paragraphs into the article, for readers bothering to scroll that far down below the fold, the Times admitted that “most research suggests that children infected by the coronavirus are at low risk of becoming severely ill or dying”, even though the answer to the questions of “how often they become infected and how efficiently they spread the virus to others” were “not definitively known.”

Of course, that was just another way of saying that the scientific evidence leaned heavily in favor of reopening schools.

The New York Times vs. Science

The link the Times provided in the sentence admitting that the risk to children appeared low was to a May 5 article by Apoorva Mandavilli titled “New Studies Add to Evidence that Children May Transmit the Coronavirus”. That article reported on two new studies that offered “compelling evidence that children can transmit the virus”. Despite falling short of having “proved it”, the evidence was “strong enough to suggest that schools should be kept closed for now” according to “many epidemiologists”.

Essentially, Mandavilli was claiming that the science had shifted since early May, when science writer Gina Kolata reported in the Times under the headline “Did Closing Schools Actually Help?” that there was “no clear way to figure out which of the lockdown measures made a difference in slowing the spread of Covid-19”, which raised the question, “Was it necessary to shut down schools?”

Randomized controlled studies to resolve such questions might be feasible, Kolata wrote, but experts noted that “it is not always in politicians’ interest to get data from randomized controlled studies. Those who called for quickly shutting schools down would face blowback if it turned out that the closings had virtually no effect on the spread of the epidemic.”

It would certainly be understandable if politicians preferred mathematical models that supported their lockdown policies rather than controlled trials or even observational studies.

They got just such a study with the first of the two characterized by Mandavilli as being strong enough evidence to conclude that schools should be kept closed.

Published in Science on June 26, 2020, that study did not document any transmission by children in schools. Instead, researchers developed a model that, based on the assumptions put into it, “showed that preemptive school closures helped to reduce transmission” in Wuhan, China, in February.

The second study upon which the Times rested its case had not yet been peer reviewed but was posted online by its author. (Shortly thereafter, it was published on the preprint server medRxiv.) For the study, researchers used reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays to determine viral loads in patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

PCR tests do not directly measure viral loads, but the “cycle threshold” serves as a proxy measure of the amount of viral RNA present in a sample. The tests work by cyclically amplifying the viral RNA, and the fewer the cycles required to reach the threshold for a positive result, the greater the amount of viral RNA is inferred to be present in the sample.

What the researchers found was that “viral loads do not differ significantly in three comparisons between young and old age groups”. They concluded that “a considerable percentage of infected people in all age groups, including those who are pre- or mild-symptomatic, carry viral loads likely to represent infectivity.”

They urged caution in lifting lockdown measures, stating that “there is little evidence from the present study to support suggestions that children may not be as infectious as adults.”

They could just as well have written that there was little evidence from their study to support suggestions that schools should remain closed.

All they had shown was that children could potentially carry and transmit SARS-CoV-2. They described this as “likely”, but a cycle threshold value correlating with infectiousness in children had not been established.

With respect to that question, Mandavilli reported that “there is a significant body of work suggesting that a person’s viral load tracks closely with their infectiousness.”

That was her way of acknowledging that similar viral loads in children and adults as inferred by PCR cycle threshold values does not necessarily mean that those children are contagious.

Several months later, on August 29, under the headline “Your Coronavirus Test Is Positive. Maybe It Shouldn’t Be”, Mandavilli finally got around to informing Times readers that positive PCR tests don’t necessarily indicate the presence of infectious virus.

Demonstrating some capacity to do real journalism, a Times investigation revealed that “huge numbers of people” were being diagnosed with COVID-19 despite “carrying relative insignificant amounts of the virus. Most of these people are not likely to be contagious.”

For diagnostic purposes, doctors do not consider cycle threshold values. Thresholds had been set arbitrarily, anyhow, without data on what value was highly likely to indicate viable, infectious virus.

The Times’ investigation found that “up to 90 percent of people testing positive” for SARS-CoV-2 “carried barely any virus”.

In other words, the vast majority of people who have been counted as “COVID-19 cases”—the numbers of which have in turn been continuously cited by lockdown advocates as justification for these extreme policies—were probably not contagious.

The threshold values of PCR tests were so high, the Times informed, that they often return a “positive” result for “not just live virus but also genetic fragments, leftovers from infection that pose no particular risk”.

That may have been news to most Americans, but it was certainly no secret within the scientific community. It is a fact about PCR tests that was known from the start by scientists.

While the May 5 Times article characterized the study on viral loads in children as providing “strong” evidence favoring school closures, the science on that was also certainly “far from settled”.

To illustrate, in a systematic review on asymptomatic and presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 published at medRxiv on June 17, researchers observed that “a positive RT-PCR test does not confirm that an individual is contagious.”

While one study had shown that higher inferred viral loads were more likely to represent infectious virus, researchers were also unable to find infectious virus beyond eight days since symptom onset despite continued high viral loads.

“This finding”, the review authors noted, “suggests persistent RNA detection represents non-viable virus that is not infectious”. Furthermore, it “demonstrates that while viral load can be predictive of transmissibility, it is not a perfect correlation.”

In a study published on June 18 in the journal Nature Medicine titled “Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections”, researchers observed that “measurable virus shedding does not equate with viral infectivity, and further evaluation is needed to determine the respiratory SARS-CoV-2 viral load that is correlated with culturable virus.” (Emphasis added.)

But never mind that.

Never mind the data indicating that children are at very low risk of severe disease or death from COVID-19.

Never mind the data indicating that children are not major drivers of community transmission.

Never mind the known harms of school closures.

A mathematical model and the finding that symptomatic children tend to have viral loads similar to those of adults were sufficient for the Times to declare the evidence was “strong” that “schools should be kept closed”.

That’s not to say that Mandavilli’s article was entirely one-sided. Anyone taking the time to read more than three-quarters of the way through could learn that there wasn’t a unanimous consensus among experts that the evidence strongly favored school closures.

While the “many epidemiologists” whose opinions were valued more highly by the Times made their appearance in the fourth paragraph, the differing view of “some other experts” made their appearance in paragraph twenty-eight.

These other experts “noted that keeping schools closed indefinitely is not just impractical, but may do lasting harm to children.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at John Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, for example, had the idea that whether to reopen schools “cannot be made based solely on trying to prevent transmission.” Instead, “a holistic view” should be taken “of the impact of school closures on kids and our families”, and the possibility should be considered that “the accumulated harms from the measures may exceed the harm to the kids from the virus.”

Dr. Nuzzo also “pointed to a study in the Netherlands, conducted by the Dutch government, which concluded that ‘patients under 20 years play a much smaller role in the spread than adults and the elderly.’”

“But”, Mandavilli immediately added, “other experts said that study was not well designed because it looked at household transmission.”

Of course, the fact that the study from South Korea also looked at household transmission didn’t stop the very same reporter in the very same newspaper from boldly declaring to the public more than two months later that children spread the virus just as much as adults!

It’s also telling that Mandavilli did not cite any experts pointing out the methodological limitations of either of the two studies she cited in her May 5 article to advocate school closures. The criterion is clear: if studies support the preferred narrative, any methodological limitations can be overlooked; whereas, if the studies don’t provide findings amenable to the desired conclusion, the limitations must be emphasized.

In sum, neither of those two studies invalidated the body of scientific evidence referenced by Dr. Atlas, Trump administration officials, the CDC, and the AAP in urging for schools to be reopened, the preponderance of which indicated that children are at very low risk from SARS-CoV-2 and considerably less likely to transmit the virus than adults.

Conclusion

I could go on with studies whose findings favor the reopening of schools, but it would be superfluous given how the Times’ own primary sources hyperlinked throughout its articles advocating continued lockdown measures either fail to support or contradict its propaganda narrative.

America’s trendsetting “newspaper of record” would have us believe that the idea that schools should be reopened is radical, dangerous, and unscientific. The reality is that the evidence does indeed show that children are at very low risk, that they are not main drivers of community transmission of SARS-CoV-2, and that any theoretical benefits are easily outweighed by the profound known harms of continued school closures.

Well I know who I want as my lawyer! Your skills are just superb! Lets get you a radio and TV show and turn this world around, one bad article, bad journalist, bad scientist, etc. at a time!

? Thank you. I appreciate the kind words of encouragement.

Jeremy, great research and writing. Thanks.

Thanks for the feedback, Frank.